How the US Govt Accidentally Created the Golden Age of American Photography

My overview of American government goes generally like this: (1) Something happens. (2) The government passes some laws in response to it, adds on a few pork projects, and raises taxes to pay for the laws and the pork. (3) The laws (or pork) cause an entirely new problem. (4) Repeat.

The usual outcome of this cycle is that every year we have more laws and higher taxes. But every so often, some accidental side effect occurs and something awesomely good happens. So it was during the alphabet-soup days of New Deal government during the Great Depression. The accidental side effect was the Golden Age of American Photography. How it happened is rather interesting.

Farmers, the Great Depression, and the New Deal

Even before the Crash of 1929, farmers in America were struggling. American farmers produced so much food during the 1920s that prices dropped so low that they could barely support themselves. Many farmers responded by increasing production even more, trying to make up for narrower margins with higher quantities.

Once the Great Depression had begun, prices dropped so low that it often wasn’t worth the cost of transporting the crops to market. In some areas farmers burned corn instead of wood or coal in their stoves. In 1933, the American government responded by passing the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which paid farmers to NOT grow crops. The idea was that having fewer crops grown would decrease supply and raise prices, supporting agriculture. It also arranged low interest loans for farmers to buy equipment like tractors, increasing their efficiency.

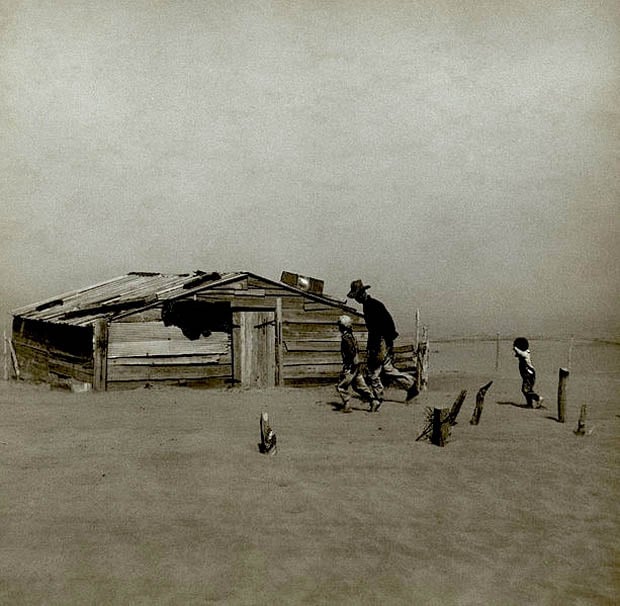

It worked as well as most government interventions. Many landowners accepted government payouts instead of planting. What hadn’t occurred to the government was that most of the actual farming was done by tenant farmers. Since the landowner was getting paid to not farm, he had no use for the tenants. Even if he continued to farm, the landowner could take advantage of the new loan programs and buy a tractor that could replace several tenant farmers who plowed with their mules.

Now thousands of tenant farmers were homeless. The Government responded, as governments do, by creating the Resettlement Administration with the goal of moving 650,000 people to new farms. The program was controversial and poorly funded. All it accomplished was building 95 camps that provided housing to about 75,000 migrant farm workers, mostly in California. To top things off, in 1936, the Supreme Court decided the Agricultural Adjustment Act was unconstitutional.

Presented with this new problem, Congress responded by creating the Farm Security Administration, which took over for both the Agricultural Adjustment and Resettlement Administrations. This program was no more popular than its predecessors at first, and seen by many as an effort to bring Socialism to American agriculture.

Politicians will be politicians, though, and Franklin D. Roosevelt (and a lot of Democratic Congressmen) was up for reelection. Bureaucrats will be bureaucrats and protect their agencies and jobs. So the FSA opened an Information Division to ‘educate’ the public about all the good it was doing. The resulting propaganda blitz was more successful than they could have hoped.

Stryker’s Plan

Rexford Tugwell, the head of the Resettlement and Farm Security Administration, hired an ex-student, Roy Stryker to “to enhance the public’s perception of the federal aid programs for the destitute.” He was to show American voters that the Depression was everywhere, that government intervention on a national level was the only way to deal with it, and that government programs were working.

In the 1930′s, there was no Internet or television. What people saw came mostly from pictures in magazines and newspapers. This was the era when glossy-photo magazines became widespread. Fortune, Look, and Life all started as photojournalism magazines in the 1930s.

Stryker’s plan was simple and effective. He knew that photographers were largely out of work because of the Depression, since newspapers and magazines had cut back staffs and people couldn’t afford either portraits or artistic photographs.

Stryker hired a number of excellent photographers on fairly simple terms. He gave them great cameras, unlimited supplies of film or plates, a small expense allowance, and some degree of artistic freedom. The photographers jumped at the chance, partly because there were so few opportunities available, partly because the work was interesting, and partly because many of them found it attractive politically.

Stryker would assign a photographer an area of the country and a general ‘shoot list’ documenting some aspect of American life in that region. He sent his photographers books and background materials before each assignment, outlined the projects in general, but then let the photographers work as they thought best.

Photographers sent all of their images to the FSA for processing. They also gave all rights to the FSA, although they could keep copies of prints or negatives for themselves. The majority of the time Stryker controlled the images totally — the negatives were sent to the central office for development and Stryker’s staff chose which images were circulated.

Stryker approached various newspapers and magazines and offered them photographic essays at absolutely no cost. Most of them, having cut back their photography departments in the Depression, were happy to use free FSA photos, of which almost 270,000 were taken.

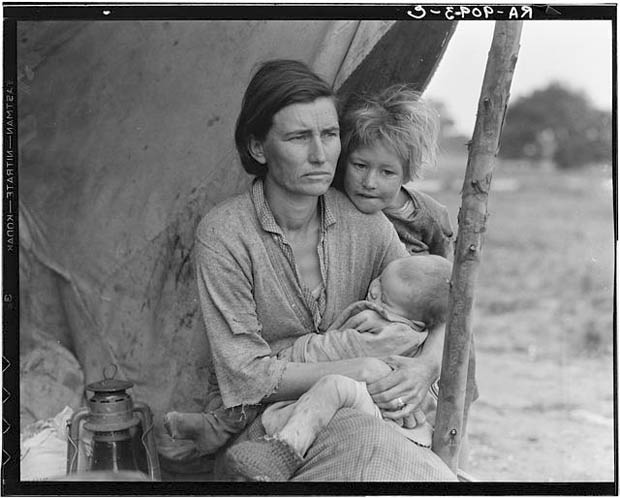

There were some exceptions where Stryker directed his photographers to work directly with regional newspapers. Dorothea Lange, for example, developed her Migrant Mother images and sent them directly to local California newspapers. That explains why the local California papers showed this photograph…

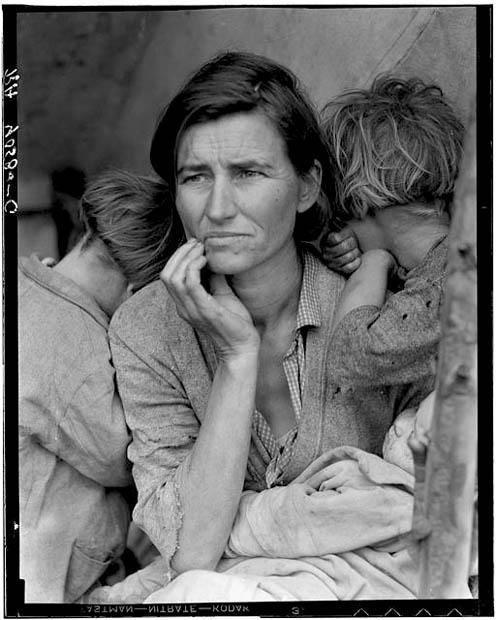

…while the rest of the country (and we today) are used to seeing this image:

In a way, the project actually went viral, although they didn’t use such terms back then. Fortune, at least, sent its own teams of photographers and journalists on similar photographic missions.

The Photographers

The list of FSA Photographers is basically a Who’s Who of American photographers. Some, like Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White, and Walker Evans were well known before their work for FSA. Others, like Arthur Rothstein, Gordon Parks, Marion Post-Wolcott, Russell Lee, and Jack Delano largely got their start through the FSA. As a group, they are some of the most influential photographers in the 20th Century.

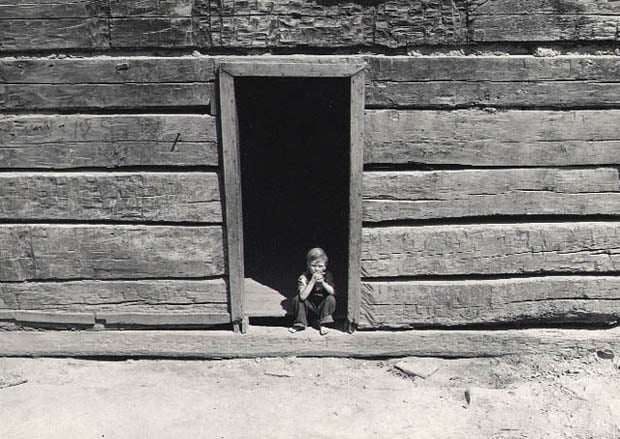

These photographers, and others who followed them, defined the genre of documentary photography. Their images defined a critical time in history and explored techniques that guided photography for a generation. They also demonstrated just how powerfully photography could influence society.

For the first time, northeastern city dwellers actually saw the living conditions of poor tenant farmers and migrant workers. People on the West Coast saw that those on the East Coast were faring no better than they.

How Did That Work Out for You, Roy?

Stryker, a man with a mission, tried to control his photographers –- but given the group he was working with, that was doomed to total failure. Walker Evans, for example, would accept an assignment, go to that general area, and then photograph whatever he found appealing, whether it had anything to do with the assignment or not.

Stryker was quite a liberal for the time, hiring several female photographers and taking the unheard of (at the time) step of hiring a black photographer (Gordon Parks). It seems he assumed they would all be grateful at the opportunity and do whatever he told them. That didn’t quite work out.

Marion Post Wolcott may have provided some of the best images of the FSA photographers, but she apparently accounted for most of Stryker’s gray hair. In one letter to Post-Wolcott, it appears he might not have been quite as liberal as he seemed, telling her, “Slacks aren’t part of your attire. You’re a woman and a woman should never dress like a man.” and “You can’t depend on the wiles of femininity in the wilds of the South” (correspondence January 13th, 1939). I would love to have seen his face when she wrote back, “Skirts do not have pockets and I’m sure you’ll agree it would be inappropriate for me to keep film rolls and filters stuffed in my blouse between my titties.”

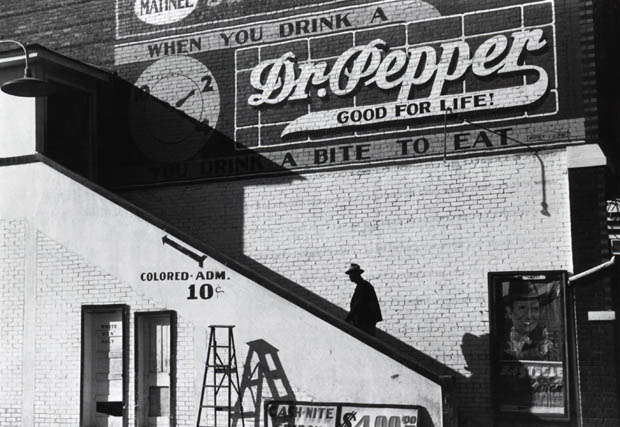

Gordon Parks (later the director of the 1970′s Shaft movies), who moved to Washington, D. C. from Seattle and Chicago, said later “I experienced a kind of bigotry and discrimination here that I never expected to experience.” He met cleaning woman Ella Watson and created his photograph “American Gothic, 1942″ as a response to the open prejudice he experienced. To his credit, Stryker simply said, “that picture could get us all fired” but didn’t destroy the image.

Marion Post Wolcott, in one correspondence, called her assignments “FSA cheesecake.” Stryker eventually said ”most of what the photographers have to do to stay on the payroll was routine stuff showing what a good job the agencies were doing out in the field. They are free to spend a day here, a day there, to get other images.” Not surprising, it was the ‘other images’ that often were the best, but probably gave our boy Roy an ulcer or three.

Post-Wolcott and others spent significant amounts of time documenting things the administration didn’t particularly wish documented, especially racial inequality and the squalid living conditions of rural African Americans.

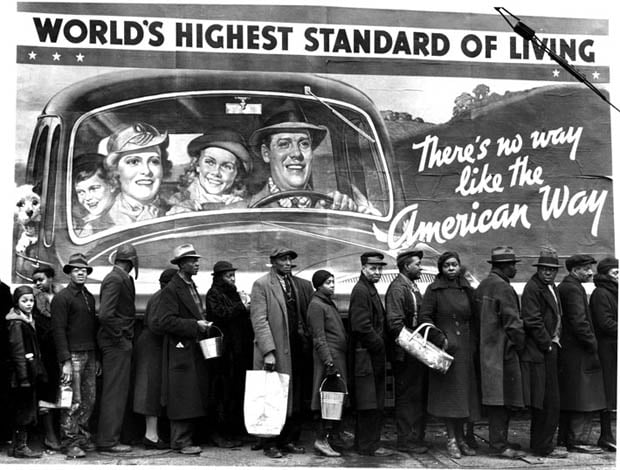

Margaret Bourke-White’s picture of African Americans waiting in a breadline under a billboard featuring a white family in their new car certainly caused some distress back in Washington — FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein had designed the billboard.

In the long run, Dorothea Lange caused probably the biggest stir. In 1941, Lange was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for excellence in photography. At the outbreak of World War II she gave up her fellowship to document the internment of Japanese Americans in relocation camps. The Army impounded and classified all of her images, most of which weren’t released until 40 years later. (They have recently been published in book form.)

The Spin-Off Books

There was similar work being done outside of the FSA. Novelist Erskine Caldwell wrote controversial novels of the Old South. His wife, Margaret Bourke White, was a premier photographer of the day, the first staff photographer for Fortune Magazine. The two travelled through the South creating the book You Have Seen Their Faces featuring her photographs and his captions. The book, published in 1937, was widely read and critically acclaimed. Later, when it was found that Caldwell and Bourke-White had made up the photograph’s captions, which appeared to be factual, the book was discredited to some degree.

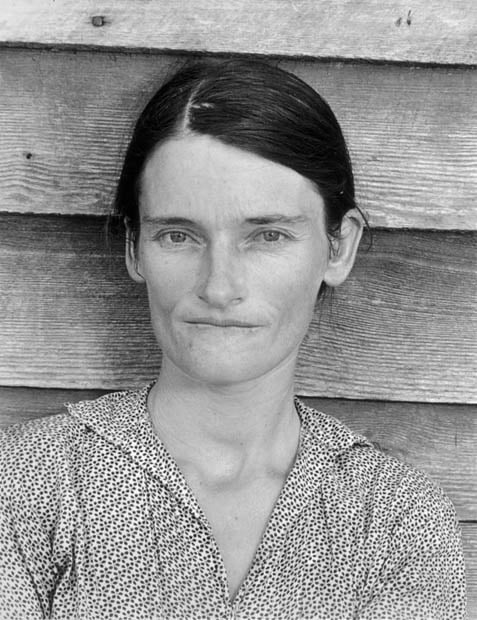

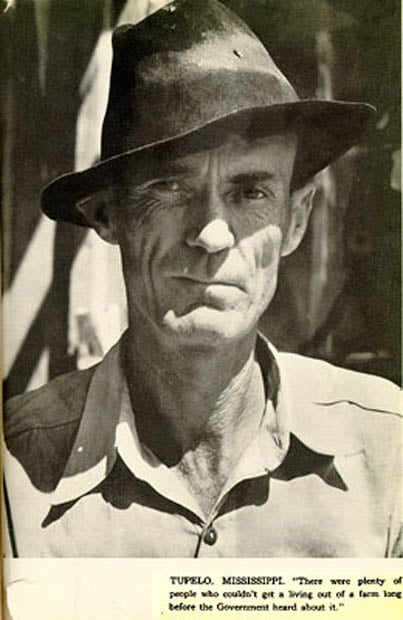

In one of the more bizarre stories of depression-era photography, Fortune Magazine writer Charles Agee talked the magazine into letting him spend several weeks in rural Alabama, supposedly reporting on the recovery of cotton farming. He also talked them into hiring photographer Walker Evans to take the photographs. Evans was at the time an FSA photographer. It is unclear if he was on loan to Fortune, between assignments, or most likely double-dipping employment. In any case the photos taken ended up in the Library of Congress archives.

Agee was very liberal (he later described himself as “a great deal more a communist than not”) and apparently hated his job at Fortune. He wrote the article far longer than the magazine could possibly publish and from a subversive point of view he knew they would not publish. As he expected, the magazine killed the story. He and Evans published it in book form (Let Us Now Praise Famous Men) in 1941, but it was not immediately popular since it was felt to be a knock-off of You Have Seen Their Faces. It was republished in 1960, and several times since, and to this day is considered one of the greatest photo documentary works ever made.

The Outcome

Despite the amazing work done by the FSA photographers, the agency itself remained constantly controversial. In 1943, Congress demanded it be disbanded and its services reorganized into existing bureaucracies. Stryker, fearing that enemies of his agency would destroy all of the photographs, donated 107,000 negatives to the Library of Congress before the agency disbanded. So in the sense of its original purpose, to show the Agency was doing great work, the project failed.

Stryker, interestingly enough, was immediately hired by Standard Oil Company to undertake a similar project to repair their tarnished reputation. He used several of his FSA photographers in this work, collecting 67,000 images over 8 years.

The subjects of the photographs didn’t benefit directly. After Lange’s Migrant Mother images appeared in California papers, tons of food were delivered to the migrant camp. Florence Owens Thompson, the woman pictured in Migrant Mother, had already moved to a new camp, trying to find work. The subjects of Evans and Agee’s book never benefitted (and their offspring remained bitter about their ‘exploitation’ for many years).

In fact, generally the subjects of the photographs were not impressed by either the photographer’s or government’s efforts on their behalf.

They simply endured and persevered, generally with dignity and pride.

The photographers, however, benefitted greatly. Dorothea Lange became the first fine art photographer on the faculty of the California School of Fine Art. Gordon Parks’ career can’t be covered in a few sentences: he was remarkably successful as a photographer, filmmaker, writer, and composer. Walker Evans became a writer for Time magazine and a faculty member at Yale University School of Fine Art. Arthur Rothstein was director of photography for Look magazine. I could go on for quite a while: the FSA photographers were among the most successful American photographers of the 20th Century.

Whether or not you think the program made a social difference probably depends more on your current politics than anything else. But what it did provide was amazing documentation of what life was like during the Great Depression. Anyone who feels sorry for themselves in the current hard economic times just has to look at those images for a while to feel perhaps things aren’t so bad today.

About the author: Roger Cicala is the founder of LensRentals. This article was originally published here.